Every year, on 25 April, Australians and New Zealanders commemorate Anzac Day – a national day that honours those who have served and died in all wars and conflicts and acknowledges the contribution and suffering of all those who have served their country. The day is marked by commemorative activities such as a traditional dawn service and parades in which serving members, veterans, their families and descendants march in recognition of military service and sacrifice. Many family members and relatives choose to wear the military medals and decorations awarded to their ancestors.

Although “Anzac” is a familiar word to Aussies and Kiwis, its origins are traced back more than a century to the First World War, when the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (A.N.Z.A.C) was formed. As colonial subjects of the British Empire, the ANZACs volunteered to fight for their King and Mother Country against the Central Powers, comprised of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. The ANZACs won fame during the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, where they fought against the Ottomans, as well as in the Middle-East and on the Western Front in Europe.

Approximately 417,000 Australians volunteered to fight in WWI, from a total population of fewer than 5 million people. Consequently, millions of Australians today have ancestors who fought in the Great War. As a result of the Centenary of the First World War (2014-2018) there has been renewed interest in family history related to military service, especially with regard to researching service records and military medals.

What medals were awarded during WWI?

As part of the British Empire, Australians were awarded Imperial medals and decorations for campaign service, gallantry and bravery. The most commonly awarded campaign medals for WWI were:

1914-1915 Star

1914-1915 Star

The 1914-1915 Star was awarded for campaign service in an operational theatre between 5 August 1914 and 31 December 1915. Those ANZACs who took part in the Gallipoli campaign between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916 were awarded the Star. It was never awarded alone. A recipient of the 1914-1915 Star would also be eligible to receive the British War Medal and Victory Medal.

British War Medal

The British War Medal was awarded for 28 days’ mobilised service in an active theatre of war between between 5 August 1914 and 11 November 1918. It is the most awarded medal of WWI.

Victory Medal

The Victory Medal was instituted to commemorate the Allied victory. It was awarded to personnel who entered any theatre of war between 5 August 1914 and 11 November 1918 (no minimum service duration applies). This medal was never awarded by itself, but always in conjunction with (at least) the British War medal and (if eligible) the 1914-15 Star.

These three medals are found mainly in two configurations, namely the ‘WWI Pair’ (British War Medal, Victory Medal) or the ‘WWI Trio’ (14/15 Star, British War Medal, Victory Medal). As a rule of thumb; if a person enlisted in 1914 or 1915 and served at Gallipoli, he/she would most likely have received the Trio. Alternatively, if he/she enlisted after 1915, the Pair is most likely to have been awarded.

It is important to note that these three medals are the most common because they were awarded for campaign service. In other words, all who took part in the War between specific dates and for a specific duration were awarded campaign medals. On the other hand, individual acts of gallantry or bravery were recognised with another group of medals, called decorations. Many fewer decorations were awarded compared to campaign medals, and as a result they are much rarer. Such decorations include the Military Medal (MM), Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) and Military Cross (MC). The most prestigious British decoration for gallantry is the Victoria Cross (VC).

How do I know which medals my ancestor received?

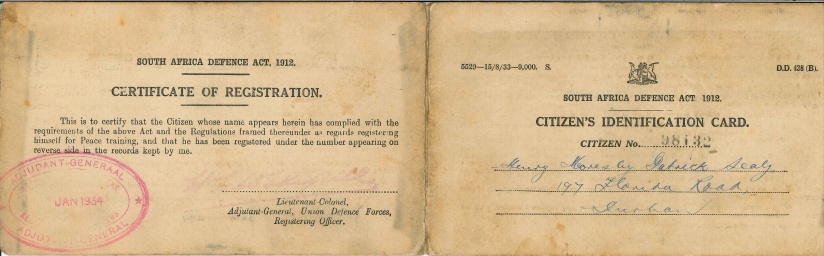

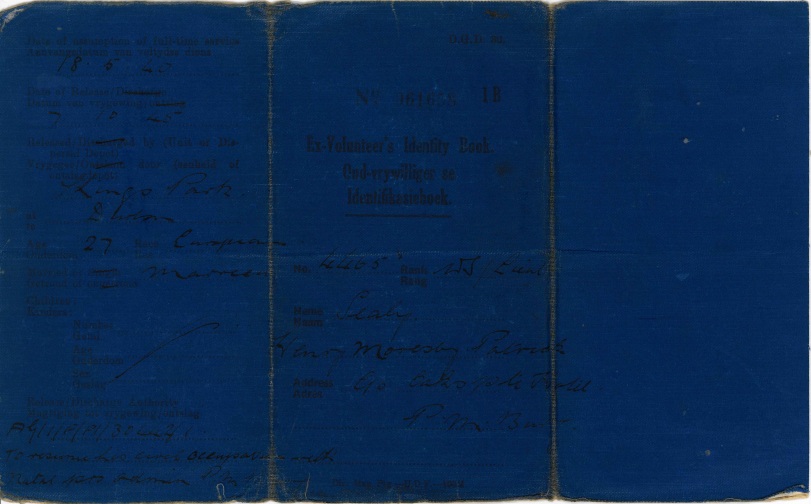

The best place to start your search for medal entitlements (i.e., which medals your ancestor received) is to track down his/her service record. Fortunately, most Australian WWI service records have been scanned and digitised. They are available (and searchable!) through the National Archives of Australia’s website.

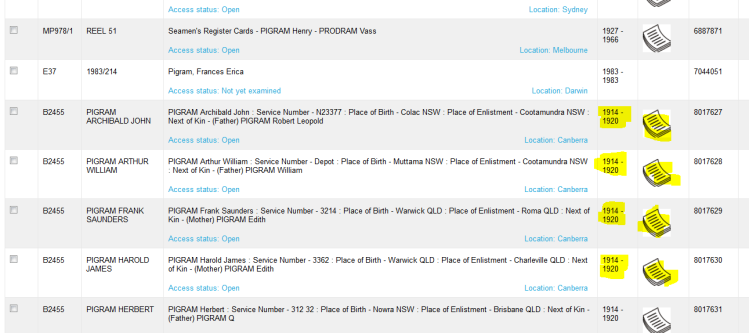

Once on the National Archives homepage, look for the search bar and enter your ancestor’s details. Useful search terms include full names, surname and service number. Once you have entered a search term and clicked the search button, the search results will be displayed. There will likely be more than one result, so scroll through them until you find your relative. For WWI service records, look for the date range “1914-1920” and an icon resembling a sheaf of papers (highlighted below). This icon indicates that records have been digitised and are available for you to view.

An example of search results from the NAA website

After clicking on the digital records icon, a new window will open with several scanned and photographed pages of records. The records typically include enlistment papers, embarkation records for troopships, disciplinary records, correspondence and medical records. This is a wonderful way to discover the history of your ancestor and it is well worth poring over each page to piece together the timeline of their wartime experience. Surprising details can often be found, although they can be difficult to decipher due to the handwriting of some military clerks.

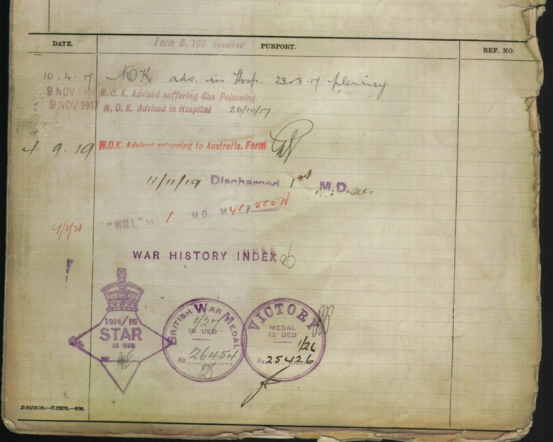

The medal entitlements page will normally be towards the end of the collection, and is easily recognised by a series of three stamps, like the ones pictured below:

Note the three stamps in the shapes of the various campaign medals

The three stamps represent the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and the Victory Medal. If a stamp has a number inscribed in it, it means that the particular medal was awarded. If a medal has the letters “N/E” inscribed, it means the person was Not Eligible to receive that particular award. In the example pictured above, it can be seen that the person in question was awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal, but was not eligible to receive the 1914-15 Star.

Not all WWI service records contain these medal entitlement stamps. In such a case reading through the service records and piecing together dates and duration of service can provide hints about which medals a person would have received. For example, if service records indicate enlistment after 1915, the person in question would most likely have been awarded the WWI pair (i.e. without the 1914-1915 star). Other sources of information include the Australian War Memorial and the Department of Defence.

Once you have determined which medals were awarded to your ancestor, you can purchase replica medals to wear on appropriate occasions, such as Anzac Day and Remembrance Day. The cost of a set of mounted replica medals can range between A$80 – A$200. Note that when wearing a relative’s medals, they should be worn on your right chest (since the medals were not awarded to you, they may not be worn on the left chest).

Feel free to leave any comments or questions below.